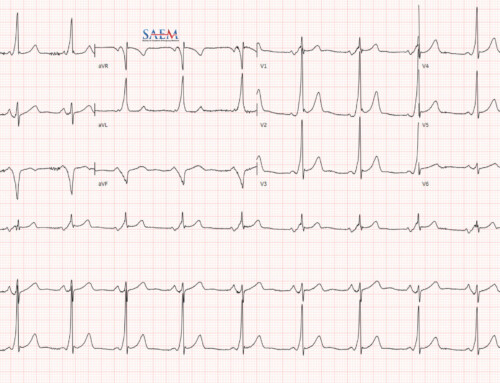

A patient presents to your ED with an all too common complaint – chest pain. After a focused history and physical exam, you have an extremely low clinical suspicion for thoracic aortic dissection, pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, pneumothorax, pericarditis/myocarditis, and Boerhaave’s syndrome. When the labs (including a troponin), an ECG, and chest x-ray yield normal results, questions often arise. Can you discharge her with a single troponin if she is low risk? How do you define low risk? And lastly, does she need urgent provocative testing after discharge?

A patient presents to your ED with an all too common complaint – chest pain. After a focused history and physical exam, you have an extremely low clinical suspicion for thoracic aortic dissection, pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, pneumothorax, pericarditis/myocarditis, and Boerhaave’s syndrome. When the labs (including a troponin), an ECG, and chest x-ray yield normal results, questions often arise. Can you discharge her with a single troponin if she is low risk? How do you define low risk? And lastly, does she need urgent provocative testing after discharge?

The 2010 American Heart Association Recommendations

These questions are almost all complicated by a lack of evidence-based national guidelines. Unfortunately, the American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines do not address troponin timing or how to specifically classify someone as low risk. The AHA does recommend, however, that “it is reasonable” to discharge low-risk patients with provocative testing prior to discharge or within 72 hours.1 Since that recommendation in 2010, numerous studies have shown that provocative testing leads to an increase in cardiac catheterization without a decrease in mortality or rate of MI.2,3

Dilemma: Should we, as emergency physicians, follow the best available evidence or the only published (and seemingly outdated) national society guidelines?

ACEP’s 2018 Clinical Policy

Thankfully, the American College of Emergency Physicians has produced a clinical policy on non-ST elevation (NSTE) acute coronary syndrome (ACS) to help guide us in addressing these clinical scenarios.4 Specifically, they set out to answer 4 practical clinical questions.

“Hot off the press about non-ST elevation ACS”

American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Subcommittee (Writing Committee) on Suspected Non–ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes: Tomaszewski CA, Nestler D, Shah KH, Sudhir A, Brown MD. Clinical Policy: Critical Issues in the Evaluation and Management of Emergency Department Patients With Suspected Non-ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes. Ann Emerg Med. 2018 Nov;72(5):e65-e106. PubMed ID: 30342745

Question 1: Who is Low Risk?

In adult patients without ST-elevation ACS, can risk stratification be used to predict a low rate of 30-day major adverse cardiac event (MACE)?

- Level A Recommendations: None

- Level B Recommendations: A HEART score [MDcalc] of ≤3 predicts 30-day MACE risk of 0-2%.

- Level C Recommendations: Alternative tools such as Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) [MDcalc] can be used to predict 30-day MACE risk.

Numerous risk stratifications tools have been created, but only the HEART and TIMI score have been sufficiently externally validated. A low risk patient has either a HEART score ≤3 or a TIMI score of 0, because it predicts a <2% risk of MACE. Studies have demonstrated that gestalt alone is not sensitive enough to predict a low risk of short-term MACE, though smaller studies have shown if an ECG and troponin are added to gestalt, they may reach a sensitivity of <2%.5

Question 2: Troponin Timing and Frequency

In adult patients with suspected NSTE ACS, can troponin testing within 3 hours of ED presentation be used to predict a low rate of 30-day MACE?

- Level A and B Recommendations: None

- Level C Recommendations

- Conventional troponin test: Conventional troponin testing at 0 and 3 hours with a HEART score 0 to 3 can predict a low rate of 30-day MACE.

- High sensitivity troponin test: A single high-sensitivity troponin result below the level of detection on ED arrival, or negative (but detectable) high-sensitivity troponins at 0 and 2 hours is predictive of a generally low rate of MACE.

- High sensitivity troponin test: Low risk patients, as defined by validated accelerated diagnostic pathways (ADP; e.g. EDACS, ADAPT) that include a non-ischemic ECG result and negative serial high-sensitivity troponin results both at presentation and at 2 hours, have a low rate of 30-day MACE and thus can be discharged from the ED.

Repeat troponin testing within 3 hours of ED presentation indeed can predict a low rate of 30-day MACE. For conventional troponins, this can be done at 0- and 3-hour negative troponin results. For high sensitivity troponins, a single UNDETECTABLE value at time 0 is enough. A high-sensitivity troponin with a detectable but negative result at 0- and 2-hours also predicts a low 30-day MACE rate. The last recommendation seems similar to the second. It presents a different subset of the literature that evaluated ADPs plus an ECG and high sensitivity troponin, and confirms that this approach is similarly supported in the literature.

Of note, these studies evaluated patients at time 0, equating to arrival time in the ED. They did not look at the timing of pain onset or relief in relation to troponin timing.

Question 3: Provocative Testing

In adult patients with suspected NSTE ACS in whom acute MI has been excluded, does further diagnostic testing (eg. provocative, stress test, coronary CT angiography) for ACS prior to discharge reduce 30-day MACE?

- Level A Recommendations: None

- Level B Recommendations: If the patient is low risk and is ruled-out for myocardial infarction, there is no need to routinely perform provocative testing prior to discharge home.

- Level C Recommendations: Arrange follow-up in 1 to 2 weeks. If no follow-up is available, consider further testing or observation prior to discharge (consensus recommendation).

These recommendations seem in line with the current evidence showing that provocative testing has questionable benefit for low-risk patients, such as increasing the rate of catheterization without decreasing rate of MI or death.6–10 Of note, the primary driver for the stress testing recommendations in the 2014 AHA guidelines come from studies conducted before 2003.1

Our patient case: Because she is low-risk (we later calculated her HEART score as 2) with a non-ischemic ECG, she should not receive a stress test in the ED. Instead, she should follow-up with her primary physician in 1 to 2 weeks.

Question 4: Anti-Platelet Drugs in NSTEMI

Should patients with acute non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) receive immediate anti-platelet therapy in addition to aspirin to reduce 30-day MACE?

- Level A/B Recommendations: None

- Level C Recommendations:

- For patients with an NSTEMI, P2Y12 inhibitors and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors may be given in the ED or delayed until cardiac catheterization.

Our patient case: If our patient’s troponin is positive, she should get aspirin and heparin in the ED. However, P2Y12 inhibitors and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors are less time-sensitive and can be given at the time of cardiac catheterization.

Another Sample Case

A 63 year old man presents with atypical chest pain that started 6 hours ago and resolved completely prior to his ED arrival.His vital signs and exam are benign and his work-up is as follows: non-ischemic ECG, unremarkable chest x-ray, and negative initial troponin test. You have a very low clinical suspicion for pulmonary embolism, aortic dissection, pneumonia, pneumothorax, pericarditis/myocarditis, Boerhaave’s, or active unstable angina.

You plan to evaluate him further for ACS.

Per the 2018 ACEP clinical policy for suspected NSTE ACS, the troponin testing strategies would include:

- Scenario A (conventional troponin): Test at time 0 from ED arrival and a repeat one in 3 hours, assuming the first was negative.

- Scenario B (high sensitivity troponin): Your high sensitivity troponin level was detectable but technically negative at time 0 upon ED arrival. Thus you repeat it at time 2 hours, which yields the same result.

- Disposition: Given that his HEART score is 3 (age, moderately suspicious history, 1-2 risk factors), he is low risk per the HEART score. The patient can be discharged to his primary doctor in 1-2 weeks without < 72 hour provocative testing.

ACEP E-QUAL Podcast: Learn more about the ACEP Clinical Policy

Dr. Christian Tomaszewski (lead author of the clinical policy from UC San Diego) and Dr. Michael Ross (expert in ED observation medicine from Emory) discuss this 2018 ACEP clinical policy. Go behind the scenes of writing the policy and the take-home points .