The newest round of the 2015 American Heart Association (AHA) Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) and Emergency Cardiac Care (ECC) contains 315 recommendations.1 It is easy to be overwhelmed by this massive (275 pages) document so this post will distill what you need to know in the emergency department. This update marks the end of a 5-year revision cycle for the AHA and the shift to a continuously updated model. Current and future guidelines can now be found at ECCGuidelines.heart.org. This round lacks any of the major foundational changes seen in 2010; however, we do say goodbye to some recommendations (bye bye vasopressin).

The newest round of the 2015 American Heart Association (AHA) Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) and Emergency Cardiac Care (ECC) contains 315 recommendations.1 It is easy to be overwhelmed by this massive (275 pages) document so this post will distill what you need to know in the emergency department. This update marks the end of a 5-year revision cycle for the AHA and the shift to a continuously updated model. Current and future guidelines can now be found at ECCGuidelines.heart.org. This round lacks any of the major foundational changes seen in 2010; however, we do say goodbye to some recommendations (bye bye vasopressin).

System & Quality

Social media is now officially recommended as a method to notify potential rescuers of a cardiac arrest. Several apps are available for download such as Pulsepoint that will let you know if there is a cardiac arrest nearby.

Regionalized care for cardiac arrest is also recommended, which involves diverting cardiac arrest patients to specialized centers that provide comprehensive care. This care may include Extracorporeal CPR (ECPR), such as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and organ harvesting, both of which are given special attention in this update.

Basic Life Support (BLS)

CPR: The ratio stays the same at 30:2 for adult CPR regardless if you are doing 1- or 2-rescuer care prior to insertion of an advanced airway. Once an airway is in place, provide continuous chest compressions, ventilating once every 6 seconds. Upper limits have been added to the chest compression rate (now 100-120 per minute) and compression depth (2-2.4 inches, or 5-6 cm) – see recent PV card on CPR. Minimizing compression pauses continues to be emphasized and the concept of a compression fraction is introduced. This is the percentage of time that hands are on the chest actually performing compressions, and the goal is at least 60%.

Compression-only CPR (or cardio-cerebral resuscitation) is now considered a reasonable alternative to conventional CPR for witnessed out of hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) with a shockable rhythm. This includes providing 3 cycles of 200 continuous compressions and defibrillation with only passive oxygen administration and an airway adjunct, and should only be performed after completing adequate training in this approach.

CPR Devices

Mechanical CPR devices: Despite the increased popularity of the impedance threshold device (ITD) and mechanical CPR devices, no randomized clinical trial has shown them to be superior over manual CPR. Consequently, the AHA does NOT recommend their use over manual CPR. However, an important caveat is made with regards to “challenging or dangerous” settings such as prolonged hypothermia, a moving ambulance, the angiography suite, and during ECPR preparation. In these scenarios, a mechanical CPR device may be a reasonable alternative.

Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS)

Vasopressin is no more in the pulseless arrest algorithm. It has gone the way of atropine and so many other drugs before it. Epinephrine remains with the same dosing and frequency (1 mg every 3 to 5 minutes).

Intralipid therapy has entered the guidelines! Considered it for patients with suspected drug toxicity, such as from local anesthetics and other drugs. The recommended dosing is an initial bolus of 1.5 mL/kg of lean body mass over 1 minute followed by 0.25 mL/kg/min for 30-60 min. The maximum total dose is 10 mL/kg in 1 hour.

Ultrasound continues to be regarded as useful during cardiac arrest; however, it should never interfere with high quality CPR. There was a new indication listed in the AHA guidelines– endotracheal tube placement confirmation.

End tidal CO2 continues to take on a more important role in addition to endotracheal tube placement confirmation. Persistently low levels in the intubated patient after 20 minutes of CPR are strongly associated with a poor prognosis and should be only one component of a multimodal approach in determining whether to terminate resuscitation. See recent PV card on end tidal CO2 monitoring.

Titration of oxygen administration: The maximum possible inspired oxygen should be given during CPR. After ROSC, however, it should be titrated to maintain an SpO2 of at least 94% as before.

ECPR can be used in select patients when local resources can support it. Remember that there is still no high-quality study that compares ECPR to conventional CPR.

ROSC

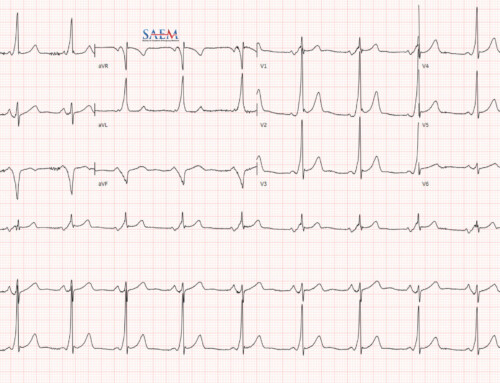

Early coronary angiography has a new indication. Not only is it indicated for ST-elevation MI (STEMI) patients but it is also indicated for those WITHOUT ST segment elevation but have a high concern for an acute coronary event. It is specifically recommended that a poor neurologic status should not factor into the decision to perform angiography as early prognostication is very unreliable.

Target Temperature Management (TTM): This is the new name for “therapeutic hypothermia.” It is recommended for all comatose patients for at least 24 hours. The goal temperature range is 32-36 degrees Celsius. Pre-hospital induction of hypothermia with cold IV fluids is not recommended.

Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS)

The CAB approach has been solidified as the preferred approach for pediatric resuscitation, similar to ACLS recommendations. The pediatric chest compression rate is now the same as adults at 100-120 per minute, as is the maximum compression depth (2.4 inches or 6 cm).

Epinephrine and targeted temperature management continue to be recommended for pediatrics.

Atropine has been removed from routine rapid sequence induction (RSI) pre-medication recommendations. Remember that it should still be used if there is evidence of bradycardia though, at a dose of 0.02 mg/kg. Further, the old minimum 0.1 mg dose of atropine has been removed.

Intravenous fluid bolus: The initial pediatric fluid bolus for pediatrics remains at 20 mL/kg. Based on a 2011 New England Journal of Medicine publication in Africa,2 if you are working in a resource-limited setting, this should be done very cautiously as it was shown to worsen outcomes.

Want more? Read the full 2015 AHA guidelines.