A 66-year-old otherwise healthy man presents by Emergency Medical Services (EMS) after being found unconscious on the ground. On arrival to your emergency department, he is back to his baseline normal mental status and without complaints. His vital signs are within normal limits and his physical exam is unremarkable. Is it a syncope? What are the key features of his history and physical exam that should affect your medical decision making? What should this patient’s work-up entail?

Enormous practice variability exists in syncope medical decision making among emergency medicine physicians, perhaps due to a lack of externally validated clinical decision rules (CDR).1,2 Even worse, the literature is rife with conflicting evidence over specific syncope features such as the age cut-off that confers an elevated risk, or the risk of near syncope versus syncope.2–6Following is a 3-step, evidence-based framework for the evaluation and workup of syncope.

Step 1: Make Sure it is Syncope

For stable patients presenting after an episode of loss of consciousness, the first step is to differentiate between syncope, seizure, a mechanical fall, or something else unusual. Unfortunately, significant overlap exists for the commonly cited differentiating symptoms. Myoclonic jerks during syncope can be interpreted by bystanders as shaking related to seizure activity. Bladder or bowel incontinence can occur in syncope, seizure, or even in severe head trauma after a mechanical fall. Patients can also bite their tongue in all three causes of transient loss of consciousness.

Pearl: Two key evidence-based features can help differentiate a seizure from syncope. Think seizure if the patient has lateral tongue biting, especially bilateral, or postictal confusion.7

Pearl: To differentiate between syncope and a mechanical fall, ask about prodrome. A preceding prodrome helps identify syncope, while remembering falling without a prodrome is more consistent with a mechanical fall.

Confusingly, a mechanical fall with head trauma can result in retrograde amnesia, for which it may not be possible to definitively differentiate between syncope, seizure, or a mechanical fall. If clinical uncertainty exists, the patient should be worked up for two or even all three of these diagnoses.

Step 2: True Syncope Versus Symptom Syncope

In true syncope, the patient is in an asymptomatic usual state of health when he/she has a loss of consciousness and postural tone, with or without a preceding prodrome, followed by a rapid, complete, and asymptomatic recovery. If the patient has any symptoms before or after the syncopal episode, they do not have true syncope. They have syncope secondary to another disease, and they should be evaluated for the acute disease associated with their symptoms.8

For example:

- Abdominal pain and syncope?

- A rupturing abdominal aortic aneurysm with syncope as a high-risk symptom

- Cancer, a swollen leg, tachycardia, and syncope?

- Pulmonary embolism with syncope as a high-risk symptom

- Fever, cough, hypoxia, and syncope?

- Pneumonia with syncope as a high-risk symptom

- Sudden onset, worst headache of life with syncope?

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage with syncope as a high-risk symptom

- Vomiting blood and syncope?

- Upper gastrointestinal bleeding with syncope as a high-risk symptom

Syncope can be from numerous causes including benign, cardiac, and almost any other dangerous disease process. The Pulmonary Embolism in Syncope Italian Trial (PESIT) study, for example, evaluated adult patients admitted for syncope across 11 Italian hospitals.9 They discovered a 17.3% rate of PE in this population! Of note, 19.1% of patients were tachycardic, 13.8% of patients were tachypneic, and 10.7% of patients had clinical signs of deep vein thrombosis. Besides the methodologic flaw of every patient receiving either a CT pulmonary angiogram or a D-Dimer, this study included a significant number of “symptom syncope” patients. Syncope can occur because of benign etiology, arrhythmias, or pretty much any other dangerous disease. Combining true syncope with symptom syncope creates an incredibly broad spectrum of pathology and likely makes it much more difficult to create a worthwhile CDR.

Hence the difference in data in a more recent ED study that showed a mere 0.6% prevalence of PE among ED syncope patients.10

Once again, history and physical is key to evaluate for any symptoms or signs of other dangerous diseases that can cause syncope as a symptom. And just in case you are evidence-based-medicine minded, the AHA/HRS/ACC have recommended performing a detailed history and physical examination on patients with syncope with a class 1 or strong strength of recommendation.3

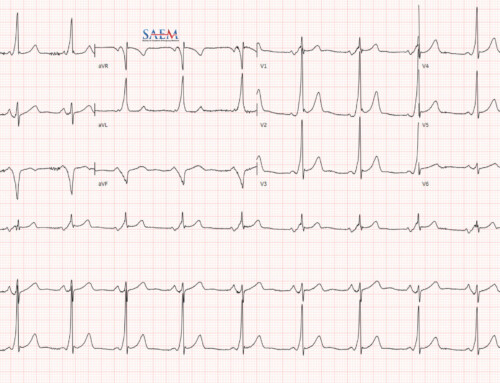

Step 3: Dysrhythmia Risk

For a case of true syncope, the third and final step is to determine the patient’s risk for dysrhythmia. An ECG should be performed on all patients with true syncope.1 While numerous criteria have come up as part of previous CDRs, I have found 6 factors that have been consistently shown to increase risk of adverse outcomes and thus require admission for telemetry monitoring and likely echocardiogram. Just use the mnemonic – FA HE HE!

- F amily history – sudden death at the young age of unknown cause or sudden death from arrhythmia at a young age1,8,11,12

- A ge – age cut-offs from various studies range from >45 yo to >90 yo. ACEP’s 2007 guidelines say it best: “Different studies use different ages as a threshold for decision making. Age is likely a continuous variable that reflects the cardiovascular health of the individual rather than an arbitrary value.” The age-related risk for arrhythmia is extremely low in patients less than 45 years old.1

- H eart disease – any history of congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, or structural heart disease1

- E xertion – syncope occurring during exertion12

- H ypotension – commonly defined as any systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg, but consider relative hypotension as well1

- E CG abnormal – see the list below, but in short, specific arrhythmia syndromes, non-sinus rhythms, prolonged intervals, and ischemic changes

Abnormal ECG Patterns

- Syndromes

- Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW)

- Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM)

- Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia (ARVD)

- Brugada

- Intervals

- Left or right bundle branch block (LBBB/RBBB)

- Left anterior or posterior fascicular blocks (LAFB/LPFB)

- Trifasicular block

- Short/Long QTc

- Short PR

- Non-sinus rhythms

- 2nd or 3rd degree AV blocks

- Ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation

- Atrial fibrillation and flutter

- Premature ventricular contractions

- Frequent premature atrial contractions

- Ischemia

- ST elevation MI

- ST changes

- ECG changes compared to previous

- Check out ALiEM’s can’t miss ECG findings for a quick reference.

ACEP’s guidelines declare that “In an evaluation of syncope, laboratory tests rarely yield any diagnostically useful information, and their routine use is not recommended.”1 If a troponin is sent on a syncope patient and found to be elevated, like in potentially all diseases, it is an independent marker for short term adverse outcomes.13

Fun Final Fact

The Canadian Syncope Rule, a new CDR which has yet to face external validation, may also be helpful in true syncope to assess dysrhythmia risk.14Importantly, they prospectively derived their CDR among 4,030 adult syncope patients with true syncope since they excluded patients with the following serious adverse events identified during the index ED visit. The excluded the following

- Death

- Arrhythmia, MI, symptomatic structural heart disease

- Dissection, pulmonary embolism, subarachnoid hemorrhage, severe pulmonary hypertension, or anemia

- Any other serious conditions causing syncope or procedural interventions for the treatment of syncope

After some complex statistics, they created a scoring tool for the 30-day adverse outcomes with 9 specific predictors of varying values. These 9 predictors and the estimated risk profiles are listed below:

Read more about the Canadian Syncope Risk Score.

Summary: Syncope in 3 Easy Steps

- Make sure it’s syncope

- Consider true syncope versus symptom syncope

- Assess the patient’s dysrhythmia risk – “FA HE HE” and Canadian Syncope score

Image Credit: The Faint by Pietro Longhi, c. 1744. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art.

References

- Huff JS, Decker WW, Quinn JV, et al. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with syncope. Annals of emergency medicine. 2007;49(4):431-444. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17371707

- Serrano LA, Hess EP, Bellolio MF, et al. Accuracy and quality of clinical decision rules for syncope in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(4):362–373.e1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20868906

- Shen WK, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Patients With Syncope: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2017;136(5):e25-e59. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30412778/

- Bastani A, Su E, Adler D, et al. Comparison of 30-Day Serious Adverse Clinical Events for Elderly Patients Presenting to the Emergency Department With Near-Syncope Versus Syncope. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;73 (3):274 – 280. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30529112

- Sun BC, Derose SF, Liang LJ, et al. Syncope Risk Score: Predictors of 30-Day Serious Events in Older Patients With Syncope. Ann Emerg Med. 2009 Dec;54(6):769-778. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19766355

- Probst MA, Su E, Weiss RE, et al. Clinical Benefit of Hospitalization for Older Adults With Unexplained Syncope: A Propensity-Matched Analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;74(2):260-269. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31080027

- Sheldon R. How to Differentiate Syncope from Seizure. Cardiol Clin. 2015 Aug;33(3):377-85. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26115824

- Quinn J. Syncope. In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski J, Ma O, Yealy DM, Meckler GD, Cline DM. eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 8e New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2016.

- Prandoni P, Lensing AW, Prins MH, et al. Prevalence of Pulmonary Embolism among Patients Hospitalized for Syncope. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(16):1524-1531. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27797317

- Thiruganasambandamoorthy V et al. Prevalence of Pulmonary Embolism Among Emergency Department Patients with Syncope: A Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;73(5):500-510. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30691921

- Grossman SA, Fischer C, Lipsitz LA, et al. Predicting Adverse Outcomes in Syncope. Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2007;33(3):233–239. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17976548

- Koene RJ, Adkisson WO, Benditt DG. Syncope and the risk of sudden cardiac death: Evaluation, management, and prevention. J Arrhythm. 2017;33(6):533–544. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5728985/

- Reed MJ, Newby DE, Coull AJ, et al. The ROSE (risk stratification of syncope in the emergency department) study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2010;55(8):713–721. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20170806

- Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, Kwong K, Wells GA, et al. Development of the Canadian Syncope Risk Score to predict serious adverse events after emergency department assessment of syncope. CMAJ. 2016;188(12):E289-9 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27378464