Every day in the Emergency Department we see older adults with dementia who have developed delirium and are brought in because of worsening agitation, combativeness, or confusion. In order to care for them, we have to consider what the underlying cause of their agitation may be, but we also have to protect the patient and staff in case of violent outbursts. Older adults experience a phenomenon termed ‘homeostenosis’ in which their physiologic reserve and the degree to which they can compensate for stressors is narrowed, putting them at risk for delirium. This post will outline ways to prevent and de-escalate agitation in a patient with delirium, and how to treat it pharmacologically in a cautious manner to minimize side effects.

Every day in the Emergency Department we see older adults with dementia who have developed delirium and are brought in because of worsening agitation, combativeness, or confusion. In order to care for them, we have to consider what the underlying cause of their agitation may be, but we also have to protect the patient and staff in case of violent outbursts. Older adults experience a phenomenon termed ‘homeostenosis’ in which their physiologic reserve and the degree to which they can compensate for stressors is narrowed, putting them at risk for delirium. This post will outline ways to prevent and de-escalate agitation in a patient with delirium, and how to treat it pharmacologically in a cautious manner to minimize side effects.

Making the Diagnosis of Delirium

The diagnosis is made based on the presence of an acute change in mental status with inattention, and either disorganized thinking or altered level of consciousness.1 Delirium is usually multi-factorial, and occurs after an inciting event or illness in a patient who is vulnerable.

Risk Factors for Delirium

Vulnerability to delirium arises from a number of predisposing factors, including:2

- Dementia or cognitive impairment

- Prior delirium

- Functional, hearing, or visual impairment

- Multiple comorbidities, or severe medical illness

- Depression

- Prior TIA or CVA

- Alcohol misuse

- Advanced age (>74)

Underlying dementia is one of the most important risk factors for development of delirium3, so the 2 impairments are often present simultaneously during a visit to the ED. If the patient’s baseline status is unknown, it can be challenging to determine how much of the impairment is due to baseline dementia, and how much is due to acute delirium. Conversely, patients who have delirium are at higher risk of developing dementia later in life.3 The presence of delirium is also predictive of a longer hospital stay4, and is an independent predictor of higher 6-month mortality.5

[Delirium serves] both as a marker of brain vulnerability with decreased reserve and as a potential mechanism for permanent cognitive damage – Inouye et al.2

Diagnosing Delirium

In patients who present with confusion and a change in behavior, it can be difficult to initially determine if they have delirium, dementia, or both, particularly if there is no prior history available in your medical record and the patient arrived by ambulance without any family members. Dementia typically has an insidious onset. It can cause impairment in cognition and memory, but it does not typically cause decreased levels of consciousness. In addition, the degree of impairment in dementia is stable over the course of hours to days, while the symptoms of delirium tend to wax and wane. It is important to distinguish whether a patient has delirium, dementia, or both. A step-wise approach can help separate out the two:

- Get collateral information. Call the patient’s family or staff at their facility to find out what the patient is usually capable of. Are they usually oriented and aware of events around them? Would they be expected to know where they are, the date, and the current president? If possible, find out the course of the recent change. Was it weeks to months, or hours to days?

- Assess their level of consciousness. Are they awake and speaking with normal speech? If not, they may be delirious. Patients with delirium can be hyperactive, appearing agitated, combative, and restless, or they can be hypoactive, with decreased alertness and responsiveness. Patients may also fluctuate between hyperactive and hypoactive states, which is referred to as mixed delirium. Delirious patients may become combative as part of their disease process. This is particularly true in those who have underlying dementia who can become disinhibited due to loss of frontal lobe function.

- Assess their degree of orientation. Ask them for their name, location, date, and the current president. If the patient cannot answer because they do not recall, but they try to cover it up in a socially-conscious way, that is more likely dementia. If they are having difficulty focusing, have poor eye contact, and responses do not make sense, it is more likely delirium.

- Perform a mini-cog. This involves asking the patient to recall 3 items (usually apple, table, and penny) at 5 minutes, and asking them to draw the face of a clock with the hands at 10 minutes past 11. The first portion tests their short term memory, and the clock-draw tests their executive function. An abnormal clock draw usually indicates dementia, though in some cases it can be due to a stroke and neglect. [How to perform a mini-cog PDF from Alzheimer’s site]

Formal tools have been validated to detect delirium in older ED patients, and could be implemented easily. Han et al6 describe a 2-step process that combines a highly sensitive delirium triage score and then a more specific brief- Confusion Assessment Method. These could be used to more formally assess and diagnose.

Searching For Causes of Delirium

If a patient appears delirious, you should search for the underlying cause. Delirium can be caused by a range of physiologic insults. The mnemonic DELIRIUM is helpful to recall some of them:7

- D rugs: Medication side effects – Frequent offenders are sedatives and psychoactive agents, as well as anti-histamines, anti-cholinergics, opiates, and alcohol. Medication interactions can synergistically lead to problems, such as serotonin syndrome, urinary retention (anti-cholinergics, and opiates), and constipation (opiates and calcium channel blockers) all of which can worsen delirium.

- E lectrolyte abnormalities – Common causes are dehydration, hyponatremia, acute renal failure, and hypothyroidism.

- L ack of drugs – Withdrawal from a medication such as opiates, benzodiazepines, alcohol may trigger delirium.

- I nfection – Pneumonia and UTIs are a common cause of delirium. Clearly meningitis and encephalitis should also be considered in the right context.

- R educed sensory input – Patients who are hard of hearing or have impaired vision and are lacking their hearing aids or glasses may develop worse delirium. Or they may appear delirious simply because they do not answer questions correctly when they cannot hear.

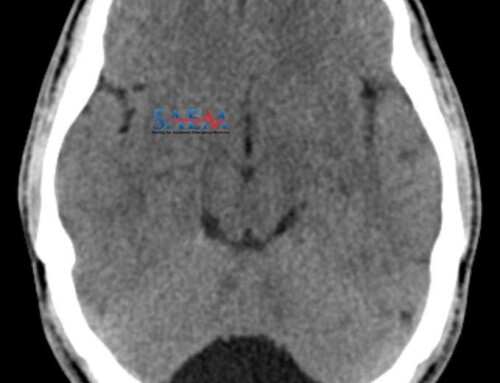

- I ntracranial pathology – An intracranial hemorrhage, CVA, or tumor may present as a change in activity level. On shift one day, a pleasant woman in her 80s was brought to me from her independent living facility after a friend found that she seemed “less feisty and not as talkative” as usual. We found she had a large intra-parenchymal hemorrhage, in the absence of any other focal neurologic deficits.

- U rinary or fecal retention – Constipation is a common problem in older adults, particularly those who are institutionalized and who have poor mobility. Fecal impaction or urinary retention can lead to delirium.

- M yocardial and pulmonary – Infarction, CHF exacerbation, COPD exacerbations, and other disease processes that cause hypercapnia or hypoxia can lead to delirium.

Management of Delirium in Older Adults

The best way to manage delirium and agitation is to prevent it.

Prevention: In patients who may be developing delirium, there are ways to help keep it from worsening.

- Treat the underlying cause. This may mean correcting electrolytes and hydration status, relieving urinary retention, treating an infection, or treating hypercapnia with NIPPV.

- Manage basic needs. Provide them with hydration and food before they become dehydrated. Older adults have a diminished thirst reflex and are prone to dehydration. Patients who are awaiting psychiatric beds may often be in the ED for extended periods, so make sure they are receiving adequate nutrition and access to water.

- Manage sensory deficits. Provide them with their hearing aids and glasses if they have them.

- Treat pain. Pain can cause delirium, so treat their pain appropriately. For fractures, nerve blocks are a great way to control the pain but avoid the systemic effects of opioids.

De-escalation and Distraction: For patients who are delirious and becoming agitated or combative, in addition to treating with the above methods, measures should be taken to de-escalate the patient to prevent them from harming themselves (though falling off the bed, or pulling out IVs) or the staff. Some hospitals have inter-disciplinary teams to address delirium. Some of the non-pharmacologic treatment modalities are listed in the appendix of.2 In the ED, not all of the suggested interventions are feasible, but some of them are and are free or easy to implement.

- Let family members stay with the patient to help reorient them, or redirect them.

- Distraction – “Busy vests” or “busy boxes” (not restraints) can provide a distraction for the patient so that they can manipulate the portions of the vest or items in a box instead of pulling on their IV or monitor leads or trying to get out of bed.

- Remove any unnecessary leads, IVs, or urinary catheters that may be contributing to the agitation.

- Turn off the TV that contributes unnecessary noise.

- If it is night-time, turn off the lights if feasible, and let the patient try to sleep. During the day time, keep lights on, and windows open.

Medications: For patients who continue to be agitated and combative despite the above measures, medications can be used to treat them. The goal for treatment is not to sedate the patient, but to manage their agitation and combativeness. For many older adults, if they are treated with the same medications and doses as younger adults, it could cause them to be over-sedated. For example, a commonly used combination of 50 mg diphenhydramine, 5 mg haloperidol, and 2 mg lorazepam would be far too much for an older adult, and could cause them to be sedated for ≥24 hours. If a patient takes an anti-psychotic medication daily and has missed it, then giving their usual ‘home medication’ is a good place to start. If not, here are some alternate options.1 Anti-psychotics are first-line. If the patient does not respond sufficiently, then a benzodiazepine can be added. However, benzodiazepines can sometimes worsen delirium.

- First line medications:

- Risperidone 1 mg PO

- Olanzapine 2.5-5 mg PO or IM

- Quetiapine 50 mg PO

- Haloperidol 1-2.5 mg PO or IM

- Ziprasidone 10 – 20 mg IM

- Second line:

- Lorazepam 0.5 mg PO, IM, or IV

- Oxazepam 10 mg PO

One exception to the above treatment algorithm is in alcohol withdrawal, in which case benzodiazepines are the treatment of choice. Higher doses may be required depending on the severity of withdrawal. Another exception is patients with Lewy Body Dementia, who may react poorly to anti-psychotics.

Summary

- Older adults are at high risk for delirium, and delirium is often unrecognized.

- Patients with dementia and cognitive impairment are at the highest risk for delirium.

- It is important to distinguish whether a patient has delirium or not. Formal tools are available to help screen for and diagnose it.

- Take measures to prevent delirium in patients who are at high risk.

- For patients who are delirious, try non-pharmacologic interventions first and involve families.

- Medications should generally be used at much lower doses than in younger adults. Certain medications, such as benzodiazepines should be used sparingly, and only if other medications such as anti-psychotics, have failed.

References

- Barrio K, Biese K. Mental Health Disorders of the Elderly. In: Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 8th ed. McGraw-Hill Education / Medical; 2015:1958-1962.

- Inouye S, Westendorp R, Saczynski J. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):911-922. [PubMed]

- Fong T, Davis D, Growdon M, Albuquerque A, Inouye S. The interface between delirium and dementia in elderly adults. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(8):823-832. [PubMed]

- Han J, Eden S, Shintani A, et al. Delirium in older emergency department patients is an independent predictor of hospital length of stay. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18(5):451-457. [PubMed]

- Han J, Shintani A, Eden S, et al. Delirium in the emergency department: an independent predictor of death within 6 months. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(3):244-252.e1. [PubMed]

- Han J, Wilson A, Vasilevskis E, et al. Diagnosing delirium in older emergency department patients: validity and reliability of the delirium triage screen and the brief confusion assessment method. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(5):457-465. [PubMed]

- Marcantonio ER. Delirium. In: Pacal JT, Sullivan GM, eds. Geriatrics review syllabus: A core curriculum in geriatric medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: American Geriatrics Society; 2010.