IDEA Series: Specialised Lectures in Emergency Medicine (SLEM) – A virtual conference to strengthen EM education in the developing world

The Problem: Emergency Medicine (EM) in Pakistan has moved from developing to developed stage in the last decade [1]. As the specialty evolves in Pakistan and other countries, there is a need to improve and assimilate novel learning methods to elevate education standards. The COVID-19 pandemic catalyzed the routine use of video-conference platforms such as Zoom. Virtual educational programming offers the opportunity to leverage educational resources across space and time, foster collaborations, and improve knowledge, clinical and evidence-based practice globally.

The Innovation

Specialised Lectures in Emergency Medicine (SLEM) is a virtual program for learning, collaboration and social engagement. The program invited experts from internationally acclaimed institutes with varying interests to present their experiences, observations, opinions, and protocols. It is an innovation that is based on a community of practice merged with the need-based assessment of a young EM residency program in a developing country.

The Learners

The target learners were EM residents and physicians practicing in the emergency department. The presenters were selected based on their experience, Free Open Access Medical (FOAM) educational materials, research, blog posts, and presentations from reputable conferences.

Group Size

SLEM accommodated 50-100 participants.

Materials

Our activity utilized simple, readily available resources. The following materials are needed:

- Video-conference platform: We used Zoom, a proprietary video-conferencing software program. The free plan allows up to 100 concurrent participants, with a 40-minute time restriction. Users have the option to upgrade by subscribing to a paid plan. The highest plan supports up to 1,000 concurrent participants for meetings lasting up to 30 hours. For SLEM, the paid subscription was necessary to accommodate up to 1 hour long lectures for some topics. Because of the risk of disruptive, non-invited participated, we recommend enabling the waiting room function, whereby only registered participants could join.

- Internet connection: A stable internet connection is a must. In order to avoid connectivity issues with Wifi, the event administrators broadcasted from an ethernet-connected computer.

- Engagement team: We formed a team including 5-6 residents to engage other participants and ask questions of the speakers relevant to local practice. This effort enhanced psychological safety for other participants to speak up, ask questions, and participate in the conversation following lectures.

- Security squad: We formed a separate team of 4 residents to oversee any non-registered participants joining the video-conference, who may generate security issues.

- Video library: All the lectures were recorded so that they can be referenced later by the residents.

Description of the Innovation

Speaker Identification: SLEM lecture presenters were individually approached through a defined methodology depicted in Figure 1. The program started in April 2021. The selection of the presenters was based on their published FOAM resources and scores of each were reviewed on an objective grading system that was adopted from Academic Life in Emergency Medicine (ALiEM) [2]. In addition to their content, additional factors considered included: the supporting evidence cited in their content, the referencing of their content in peer and non-peer reviewed publications, their content gradation as per the Social Media Index, and review of their faculty profiles and areas of expertise from the university website. The presenters also recommended their peer faculty who were similarly reviewed and assessed prior to the designation of the topic followed by the talk.

Topic Selection: Topics were selected based on the speaker’s previous academic lectures and area of expertise, although occasionally the presenter chose a different topic approved by the organizers based on their academic profile. Topics were selected based on disease prevalence in Pakistani EDs, published literature describing gaps in resident education and expertise, and gaps identified during academic core meetings. The presenters were then approached through either their official email address, the email address from their FOAM website, Twitter, Facebook, publications, or institution website. Upon confirmation of the lecture, an online calendar invitation including a Zoom link was shared with the presenter.

Publicity: The conference was widely advertised with promotional materials [brochure, video]via Twitter, WhatsApp, and the national EM society listserv.

Video-conference Schedule: Sessions took place virtually, starting with a 5-minute introduction of the presenter, followed by a 45-minute talk, and closing with a 15-minute question and answer session.

Lecture Evaluation: Post-session evaluation forms were shared with the residents and faculty after each session to gather feedback. Each SLEM lecture’s quality was evaluated through the internationally validated, reduced version of the Students’ Evaluation of Educational Quality (SEEQ) [3]. Originally developed by Marsh et al., this tool assesses the level of student satisfaction with teacher effectiveness to improve teaching quality. It has an excellent reliability, internal consistency, validity, and quality and has the flexibility to fit into individual teaching contexts. Reduced SEEQ is useful for quickly gathering data and decreasing the risks of item nonresponse and has been extensively studied at the postgraduate level. The variables weighted most heavily for SLEM included:

- Learning

- Individual rapport

- Enthusiasm

- Organization

- Breadth

- Group interaction

- Overall rating

At the conclusion of the overall event, each participant had the opportunity to complete an online evaluation developed using Google Forms to provide feedback to the organizers. Several participants were selected for a brief, follow-up interview to explore their reactions and gain additional feedback.

The first SLEM virtual conference was successfully held July 20, 2023. Additional materials for the activity are available upon request by contacting Dr. Shahan at [email protected].

Figure 1: SLEM Conference Planning and Design

Lessons Learned

SLEM has played an important role in strengthening the academic component of our developing residency. Despite the sessions being held virtually and after hours, the resident and faculty were engaged and reported increased knowledge and clinical practice improvement. Our target audience of trainees and junior to mid-level faculty especially appreciated the SLEM conference, as they appreciated tips from more senior clinicians. Additionally, the planning team developed strong bonds through the process, paving the way for future collaboration. The sessions overall contributed to the formation of a global community of practice by engaging speakers at different institutions around the world.

During planning, we faced challenges coordinating across time zones. Sending electronic calendar invitations explicitly stating the time zone along with the time was important for avoiding errors. Deploying our security teams, a robust registration system, and the waiting room function in Zoom were important strategies for avoiding disturbances to the event. Our engagement team also helped keep our participants active despite the large audience and virtual format.

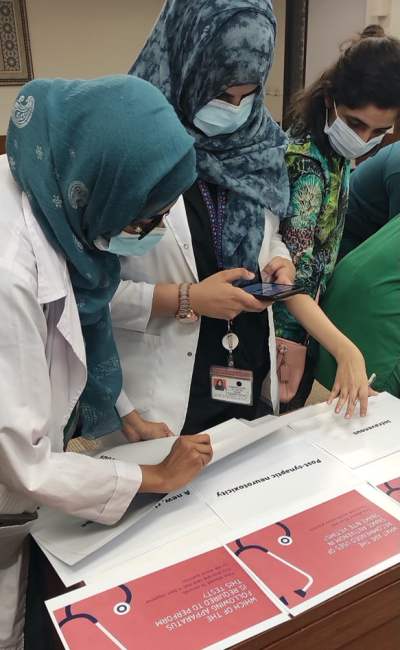

Figure 2. Team SLEM after successfully executing the SLEM conference

Theory behind the innovation

The educational theory supporting our initiative was community of practice [4]. The underlying principle highlights that learning occurs through social engagement in authentic contexts. The SLEM presenters and audiences (EM residents and faculty) were all individuals with shared interests and personal experiences relevant to the practice of EM.

Closely related, social cognitive theory also underpins the SLEM innovation. This theory postulates that learning occurs in social contexts and involves the reciprocal interaction of the individual, behavior, and the environment [5]. SLEM provided learners with the opportunity to receive experiential and tacit knowledge directly from clinical experts, which can then be applied, tested, and adjusted in their own environments. SLEM created a venue for dissemination of perspectives, discussion, and international practice change.

References

- Waheed S, Ali N. Chief Resident Election of Emergency Department (CREED)–An innovative approach to fair and bias-free chief resident selection in a residency program. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences. 2022;38(6):1717. PMID 35991269

- Brindley PG, Byker L, Carley S, Thoma B. Assessing on-line medical education resources: A primer for acute care medical professionals and others. Journal of the Intensive Care Society. 2022;23(3):340-4. PMID 36033246

- Coffey M, Gibbs G. The evaluation of the student evaluation of educational quality questionnaire (SEEQ) in UK higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. 2001;26(1):89-93.

- Schwen TM, Hara N. Community of practice: A metaphor for online design? The Information Society. 2003;19(3):257-70.

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational behavior and human decision processes. 1991;50(2):248-87.

In many parts of the world, emergency medicine is just beginning to emerge as a specialty. In Pakistan, for example, it was introduced as recently as 2012. Hands-on training in the management of critically-ill medical and trauma patients is imperative for adequate preparation of board-certified emergency physicians, but accurate simulation can be hard to come by in developing nations. There are very few training programs and dedicated centers for healthcare professionals, and even fewer that have simulation [1]. High-tech simulation equipment is often cost-prohibitive; a mobile, low-tech simulation lab could potentially address the need for advanced training in resuscitation for emergency physicians training in under-resourced hospitals.

In many parts of the world, emergency medicine is just beginning to emerge as a specialty. In Pakistan, for example, it was introduced as recently as 2012. Hands-on training in the management of critically-ill medical and trauma patients is imperative for adequate preparation of board-certified emergency physicians, but accurate simulation can be hard to come by in developing nations. There are very few training programs and dedicated centers for healthcare professionals, and even fewer that have simulation [1]. High-tech simulation equipment is often cost-prohibitive; a mobile, low-tech simulation lab could potentially address the need for advanced training in resuscitation for emergency physicians training in under-resourced hospitals.