SAEM Clinical Images Series: Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing

A 55-year-old female with a history of hyperlipidemia presents after a syncopal episode. She had mild nausea and diarrhea on the morning of presentation but otherwise had no prodromal symptoms before suddenly losing consciousness in a grocery store. Of note, she recalls a similar syncopal episode in the remote past, also preceded by gastrointestinal symptoms at that time. At present, she is symptom-free.

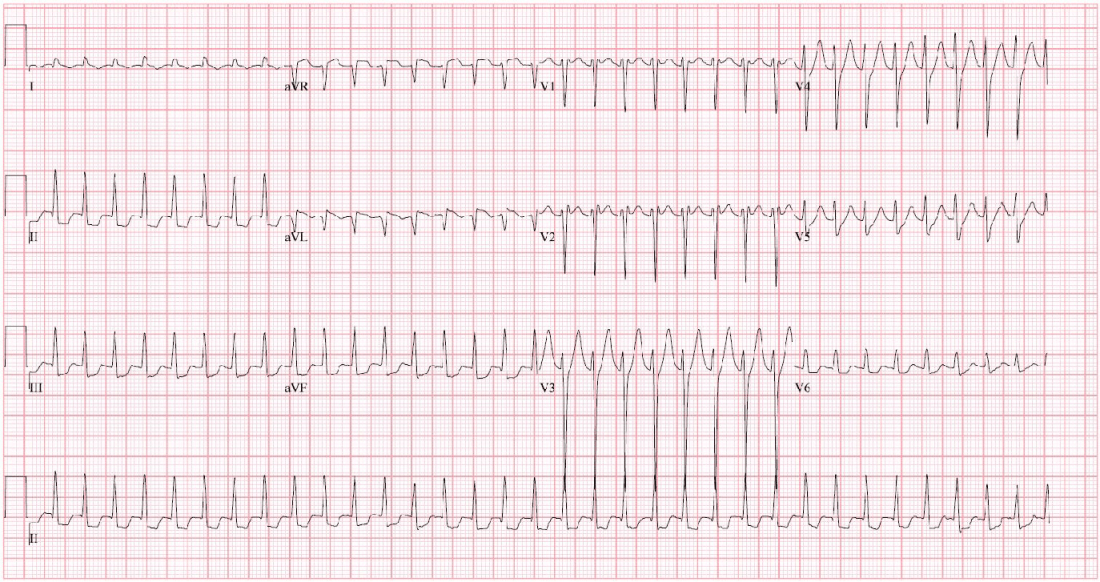

Vitals: BP 135/71; HR 52; Temp 98°F; RR 18; SpO2 100% on room air General: Tired appearing CV: 2+ peripheral pulses. Regular rate and rhythm, no murmurs, rubs, or gallops. Pulmonary: No increased work of breathing. Lungs clear to auscultation bilaterally. GI: Soft, non-distended, non-tender to palpation. Non-contributory Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome (WPW) Short PR interval (< 0.12 seconds) and slowed upstroke of the QRS complex, referred to as a delta wave, which are both seen in our patient. These particular EKG findings define a “Wolff-Parkinson-White Pattern.” WPW is a pre-excitation syndrome characterized by an accessory pathway caused by a congenital failure of cells to resorb near the AV valves. This accessory pathway conducts impulses faster than the AV node, causing a short PR interval. WPW Syndrome consists of characteristic EKG findings as well as symptomatic arrhythmias. Patients with WPW may classically present after a syncopal episode due to an arrhythmia involving the accessory pathway. Most commonly, WPW is associated with atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT) and atrial fibrillation. First-line treatment for WPW-mediated tachyarrhythmia consists of procainamide, which blocks conduction through the accessory pathway. An exception to this would be the hemodynamically unstable patient, who should be cardioverted. AV nodal blocking agents should be avoided in patients with tachyarrhythmias as they can cause increased conduction to the ventricles through the accessory pathway, leading to potential ventricular arrhythmias and hemodynamic instability. Ablation of the accessory pathway is indicated in those with symptomatic tachyarrhythmias and leads to successful remission in about 90 percent of cases.Take-Home Points

Copyright

Images and cases from the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) Clinical Images Exhibit at the 2023 SAEM Annual Meeting | Copyrighted by SAEM 2023 – all rights reserved. View other cases from this Clinical Image Series on ALiEM.