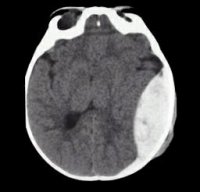

Intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) is associated with significant disability and mortality. Although evidence-based guidelines exist, many hospitals have their own institutional practice patterns, which can make it difficult to care for these patients in the ED. Dr. Debbie Yi Madhok, an emergency physician and neurointensivist, sat down with Dr. Derek Monette, the ALiEM Deputy Editor in Chief, to discuss updates in the management of ICH. This interview follows up her original popular 2017 ALiEM post on dilemmas in ICH management, and takes a deeper dive into the nuances of seizure prophylaxis, blood pressure control, and platelet transfusions. We present the podcast and key learning points.

Intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) is associated with significant disability and mortality. Although evidence-based guidelines exist, many hospitals have their own institutional practice patterns, which can make it difficult to care for these patients in the ED. Dr. Debbie Yi Madhok, an emergency physician and neurointensivist, sat down with Dr. Derek Monette, the ALiEM Deputy Editor in Chief, to discuss updates in the management of ICH. This interview follows up her original popular 2017 ALiEM post on dilemmas in ICH management, and takes a deeper dive into the nuances of seizure prophylaxis, blood pressure control, and platelet transfusions. We present the podcast and key learning points.

Indications for Seizure Prophylaxis in Traumatic Head Injury

Not every traumatic head injury warrants seizure prophylaxis. As an example, in an isolated traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage with a GCS of 11 or more, there is no indication for seizure prophylaxis. However, there are some clear indications:1–6

- GCS ≤ 10 (phenytoin is the agent of choice)

- Depressed skull fracture

- Subdural or epidural hematoma

- Hemorrhagic contusion

- Penetrating head trauma

- Seizure within the first 24 hours

What About Atraumatic Head Bleeds?

There is also no indication to give seizure prophylaxis in atraumatic head bleeds. This is important, because in this patient population, these medications are associated with elevated temperature, vasospasm – and with phenytoin in particular – worse cognitive outcomes 90 days after injury.7–11

Traumatic Brain Injury: Relevance of GCS

According to the Brain Trauma Foundation (the go-to resource for TBI evidence-based guidelines), if a head injury warrants seizure prophylaxis, medication selection is based on the severity of the TBI.

TBI severity is classified by arrival GCS:

- Severe: GCS ≤ 8

- Moderate: GCS 9-12

- Mild: GCS 13-15

Why Phenytoin?

Dr. Madhok reports that this question – “why phenytoin?” – comes up at every conference at which she speaks. In severe head injury (GCS ≤ 8), the Brain Trauma Foundation recommends phenytoin for seizure prophylaxis. This recommendation comes from a randomized, double-blind study of phenytoin versus placebo for the prevention of post-traumatic seizures. Most patients in this study had severe TBI, and given the high-quality of its evidence, the recommendation remains.12 However, for mild or moderate TBI, a number of agents may suffice, including phenytoin or levetiracetam.4

Blood Pressure Management in Intracranial Hemorrhage

For patients with ICH, tight blood pressure control is paramount. Blood pressure goals can be recalled by understanding the relationship between mean arterial perfusion and cerebral perfusion:

[Cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP), mean arterial pressure (MAP), intracranial pressure (ICP)]

Spontaneous ICH is high risk for expansion, and hematoma growth within the first 24 hours is an independent predictor of mortality.13 For these patients, the goal systolic blood pressure is <140-180 mm Hg. This can often be achieved with a nicardipine, and bolus pushes of IV labetalol may suffice while waiting on the infusion.

For traumatic bleeds, the focus shifts from lower the blood pressure, to maintaining a systolic blood pressure above 100-110 mm Hg (age-dependent range). This may help prevent secondary injury, as hypotension predicts mortality and functional outcomes in patients with traumatic ICH.14

Platelet Administration in Intracranial Hemorrhage

There remains some controversy regarding the use of platelets in patients with traumatic brain injury and current use of aspirin, clopidogrel, or other antiplatelet agents. The PATCH trial corroborated the practice of many neurointensivists – avoiding transfusion in patients presenting with an atraumatic or spontaneous ICH while already on an antiplatelet agent at home.15 Anecdotally, however, many surgeons find that a platelet transfusion can help control intra-operative bleeding. Therefore, it is still important to have a conversation with the neurosurgical team about the risks and benefits of a transfusion in patients with spontaneous ICH.

For more great talks, Drs. Yi Madhok, Mattu, Birnbaumer, Colwell, and others will be lecturing at the 2018 UCSF High Risk Emergency Medicine Hawaii conference in Maui April 8-12, 2018.